One of the most difficult problems in imaging is contrast enhancement. Let’s take a look at a biomedical example to better understand this.

Imaging in the Biomedical Industry

By the untrained eye, mammalian tissues all look pretty similar. The tissue is usually red or pink, shiny, and has areas that are darker or browner than the rest - rarely can something be determined as ‘out of the ordinary’. Generally, this doesn’t present a problem, unless a medical professional is tasked with attempting to identify "healthy" versus "diseased" tissue and other problems. Manual observations using white light reflectance are limited, so professionals turn to typical H&E stains and perhaps fluorescence.

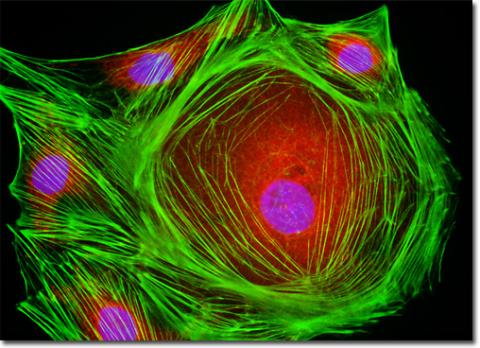

Fluorescence and Image Enhancement

Fluorescence is a common method of image enhancement. The bright signal on a black background is a great contrast enhancer, which assists medical professionals in situations such as the one mentioned above. Researchers commonly apply extrinsic fluorescent tags to label molecules of interest in the field of view. Another method involves generating labeled chimeras or transgenic animals in the lab that intrinsically express different fluorescent compounds inside the cells. These animal models - such as the rainbow mouse - are often used for cell-tracing studies in developmental or cancer research. These bright fluorescent signals on non-fluorescent backgrounds are a great contrast enhancer that assist medical professionals in situations such as the one mentioned above.

Understanding the Molecules Used in Imaging

In humans, the FDA controls what sorts of fluorescent molecules can be used and the list is very small. Because of this limitation, researchers and clinicians are looking for contrast inside the cells and tissues themselves. While all cells from bacteria to giant squid neurons are composed of the same basic building blocks- lipids, proteins, DNA, and small molecules (NADH, ATP, sugars, etc.)- the concentration of these components can vary depending on cell type. Many of these molecules emit light at certain wavelengths when excited with others. Depending on what sort of experiment you are doing, this intrinsic fluorescence can be used as your contrast agent, or can be a nuisance background if you are using extrinsic fluorescence as your contrast agent.

Intrinsic Fluorescence Sources

There are many sources of intrinsic fluorescence, including the metabolic molecules, NADH and FAD, amino acids like tryptophan and tyrosine and even the base pairs of DNA. The most abundant intrinsic fluorophores are excited in the UV wavelengths or by using multiphoton (pulsed laser) techniques. Notable exceptions are melanin, carotenoids and lipofuscin, which absorb and emit in the visible regions.

A selection of intrinsic fluorophores present in mammalian tissue.

Applications of Intrinsic Fluorescence

Intrinsic fluorescence has been used successfully to identify a number of abnormalities in humans, including Barrett's esophagus, colon cancer, lung cancer, and cervical neoplasia. At Omega, we are working with the University of Vermontto identify abnormal breast cancer surgical margins at the microscopic level using a novel multispectral imaging system. This system uses excitation at 375 nm to excite primarily the metabolic fluorophores of NADH and FAD. This ratio has been shown to be indicative of cancer. The system uses a serial array of coated fiber tips to provide spectral resolution and the tip of the fiber array acts as a confocal pinhole for spatial resolution. We have been able to characterize spectral and spatial differences between normal tissue and cancerous lesions using this system. Read our paper "Real‐time detection of breast cancer at the cellular level" for more information.